I have had a reasonable amout of success purchasing tools on ebay. While nothing beats getting to pick up a tool and look it over, being picky online can net you some pretty sweet tools. There will be misfires though. The starrett no92 in the picture below is a notable example.

I clearly saw that the spring on the micro adjust was missing, but I thought I could fix that easily. So I picked it up for just over $40.00 shipped. What I didn’t see was that the quadrant rod was bent and the rod clamp had been seriously distorted. So now I own a nice-ish looking, non-locking compass/paperweight.

So how do you avoid this? One way is to arm yourself with knowldege. Look at vintage catalogs so you know what parts should be there. There are a couple of sites with freely available scanned catalogs. The Alaskan Woodworker and Blackburn Tools both host many scans from the Rose Tool archive that is now gone from the web. Grab the catalog you want and learn what you’re looking for. This is most useful for planes and other complex tools. Then arm yourself with a tolerance for dissappointment. You are going to buy some clunkers. Get used to it.

If the thought of buying trash is distressing to you, then stick to the online sites devoted to user grade tools. Hyperkitten Tools and Patrick Leach at The Superior Toolworks are two that I buy from and I have never been disappointed by either.

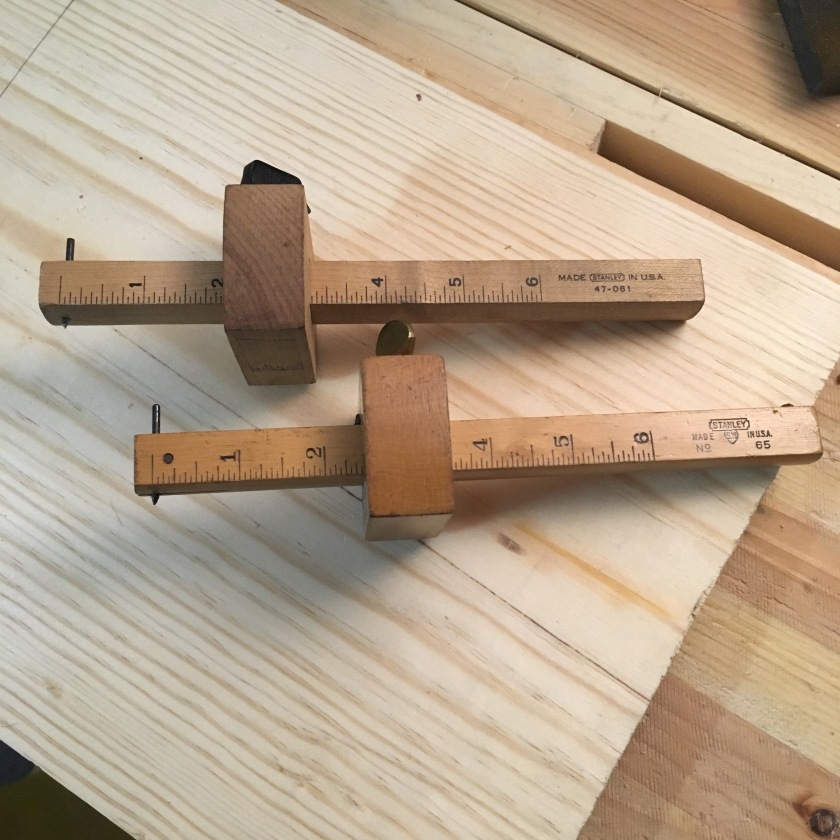

Here are some other strategies that I have found helpful. If you want a desirable tool, look around at competing manufactuers. The stanley 58 above has 80% of the functionality as the Starrett 92, while routinely selling on ebay for 1/3 the cost. If a company still makes the tool, it can be cheaper new than used, sometimes. This is particularly true of Starrett and Lie Nielsen. I have seen used versions of normal production tools of both manufacturers go for crazy high prices. Finally, if you see a tool that is going for way less than normal, chances are that there is something wrong with it and the more experienced buyers are staying away. Exceptions to rule include situations with mispellings and clear mislabelings.